Bean-counting by firelight

on C. Thi Nguyen’s The Score & Nicholson Baker's A Box of Matches

I just finished reading C. Thi Nguyen’s new book The Score alongside Nicholson Baker’s A Box of Matches. To my delight these books go together so well, here’s why:

The Score asks the question: why are rules and scoring systems super fun when I’m selling fruit for bells (a made-up currency) in the video game Animal Crossing and absolutely soulcrushing when I am counting my publications and ranking journals to get tenure? Part of the brilliance of the book is to think of the question in the first place–to realize that there’s even a throughline between games and bureaucratic torture. And he’s right, there is. Games work to coordinate people’s behavior by creating a common scoring system which sets people’s incentives and makes it clear when you’re making good moves in the game. In Animal Crossing, you’re taking care of a formerly deserted island, so you get lots of bells for doing things that make the island better like selling weeds that accumulate, and fewer bells for things that don’t. Taking care of the island and making it better is the point of the game and the game rewards you for that. My department wants me to produce scholarly work that is high impact. That’s pretty hard to measure so academic departments have figured out they can count up how many publications I had and whether they were in journals whose impact is also quantified by an “impact factor” (that has something to do with the readership of the journal and how often work in it gets cited by other scholars, yes this is a metrics matryoshka). This lets my department figure out if I was productive without having to read a bunch of papers in a field they don’t know, whose quality they can’t really evaluate. Notice how far we have drifted from the point of everything! Ok so in both games and bureaucratic bean-counting, we’ve got scoring systems and incentives that set standards for people’s behavior and make it clear when people did or didn’t meet them. One of them turns everything ineffable that you love into a set of crunchable numbers that dictates your life. The other is academic publishing. No, just kidding, I am obsessed with Animal Crossing right now and it’s really fun.

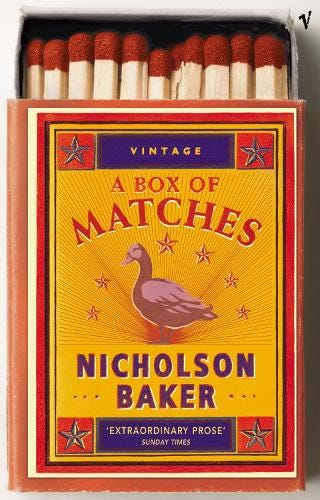

In Nicholson Baker’s 2003 novel A Box of Matches, the unnamed first person narrator wakes up every day before the sun comes up to light a fire. He gets dressed and makes coffee in the dark and pokes around gently at the kindling in the fire, and also his thoughts. Baker is one of my favorite authors ever and it’s because he is a masterful tunneler of attention. He loves really mundane stuff, like lighting a match, and then through him we get to re-see this thing we never think about ever as a little marvel. I really love that he often does it with modern things like matches or stockings or escalators or the pharmacy. Exactly the stuff that needs re-marveling.

Here’s Baker describing how it looks when you light a regular everyday match:

“When I struck it in the profundity of the dark I could see the dandelion head of little sparks shooting out from the match head and the eagerly waving arms of the new flame before it calmed down.”

Or here’s a description of deciding to take his own temperature and then doing it:

“If I didn’t know, I wouldn’t be giving my sickness its fair due, since the only real achievement of a sickness is the creation of a fever. The rest is dross.* I found the thermometer and got back in bed, leaning against the pillows, and slid the glass swizzle-stick down into the fleshly church basement below my tongue, on the right side of that fin of stretchable tissue that goes down the middle.”

Have you ever thought about your mouth as having a church basement?????

Ok back to The Score. Bureaucratic benchmarks are soul-crushing because they leave a big gap between what we actually care about and what can be measured. When we forget about the things we actually care about (like making interesting discoveries) and we write worse papers to try to get more publications, we get “value capture,” the metric eats the value. We don’t have to worry about value capture in games though because the metrics just literally are the thing we are trying to do–there’s no gap. No gap, no capture. We are susceptible to value capture because we love counting things up, and we love winning, and we love acknowledgement for doing a good little job. If you’ve ever waved your arm around so that your step-counter will tell you that you’ve hit 10,000 steps, you know about value capture.

Box of Matches is like the perfect opposite of value capture, it’s like value release. Baker shows us that actually there was this whole crackle of value to get from thinking about a match or that weird “fin” in your tongue, if you just stopped and filtered everything else out for sec. The whole book is like that!

I’ve been thinking about value capture in relation to some of the work in motivation science. For example, classic work by Locke & Latham on goal setting, suggests that setting goals that are both specific and challenging (as opposed to vague like “do your best” or too easy) improves people’s performance at tasks both in the lab like solving anagrams and proofreading text and outside it like negotiating or exercising. There are some factors that make this relationship bigger or smaller, like how committed you are to the goal and whether you set it yourself or someone else sets it for you, but the core of the idea remains. Bureaucratic benchmarks are also often specific and challenging. They don’t just make it easy to count, they also make the behavior more likely.

10,000 steps is a great example: it’s really specific and pretty hard. When I was in the thralls of a fitbit in 2016 I would sometimes walk from NYU to Brooklyn to get that thing to buzz. I was a good data point for Goal Setting Theory ,but I was also annoying. My partner eventually confiscated the stepcounter. Goal Setting Theory takes it as a given that better performance = good, but reaching the goal isn’t all that we’re after.

Here’s something really wonderful hiding in the acknowledgments of The Score:

“And to my graduate school adviser, Barbara Herman, who may not have realized it, but set my whole life on a new course when she casually, in the middle of a graduate seminar, said, “Of course there’s a difference between a goal and a purpose. When you’re playing cards with your friends, your goal is to win, but your purpose is to have fun.”

SWOON.

I personally liked reading The Score in the middle of the night and in the morning, and Box of Matches right before bed. Both of these books are great company. I knew as soon as I finished that I would miss them. I hope you liked reading about them.

yfpp,

ana

PS If you really want to make a whole adventure out of it, Phillip Pullman released a new trilogy over the past couple years set in Lyra’s universe from His Dark Materials. The first one is a prequel and the second two are sequels. Obviously they are so good. If Pullman ever reads The Score I suspect he would be extremely sympathetic to it. The third book The Rose Field, in a way makes the argument of The Score except that it’s a glittering adventure with Lyra and daemons (and gryphons!) and it takes the argument further to commodification, capitalism and the way dollars value-capture everything, especially the invisible things that make life alive.

*also “dross” is an obscure word for the impurities you get when you melt metal (yes obviously i had to google that), and second, “the rest is dross” is a reference to Ezra Pound “What thou lovest well remains, the rest is dross.” I just learned that from writing this!!!